When I returned to surfing after a 15-year hiatus, in the mid-1990s, I was living and working in New York City. My go-to spot was Long Beach, about an hour’s drive from the city on Long Island, where the waves could be good and the locals were salt-of-the-earth friendly. I came to know the boardwalk, the cheek-by-jowl bungalows, the bagel shops and barnacle-encrusted jetty rocks, the ivory gulls with their sidelong appraising looks, the jetliners passing overhead in the clear autumn skies, headed for Kennedy Airport. By the time Hurricane Sandy hit in the fall of 2012, I had been surfing there long enough to feel an adopted son’s anguish at the damage, which was extensive.

Amid rumors of bands of looters and toxic spills, I joined a caravan of fellow Brooklyn surfers and drove out to volunteer in the cleanup effort. We entered town by way of an unfamiliar roundabout route, the usual way having been cut off by flooding. The traffic lights were flashing yellow on eerily deserted streets, ruined household belongings piled on curbs like hillocks of plowed snow. Closer to the beach, we caught glimpses of the wave-shattered boardwalk, streets filled with sand, abandoned cars. Eventually we arrived at the designated meet-up spot for volunteers, a construction company’s store in a strip mall. It was nervously agreed that we would be sure to leave before nightfall.

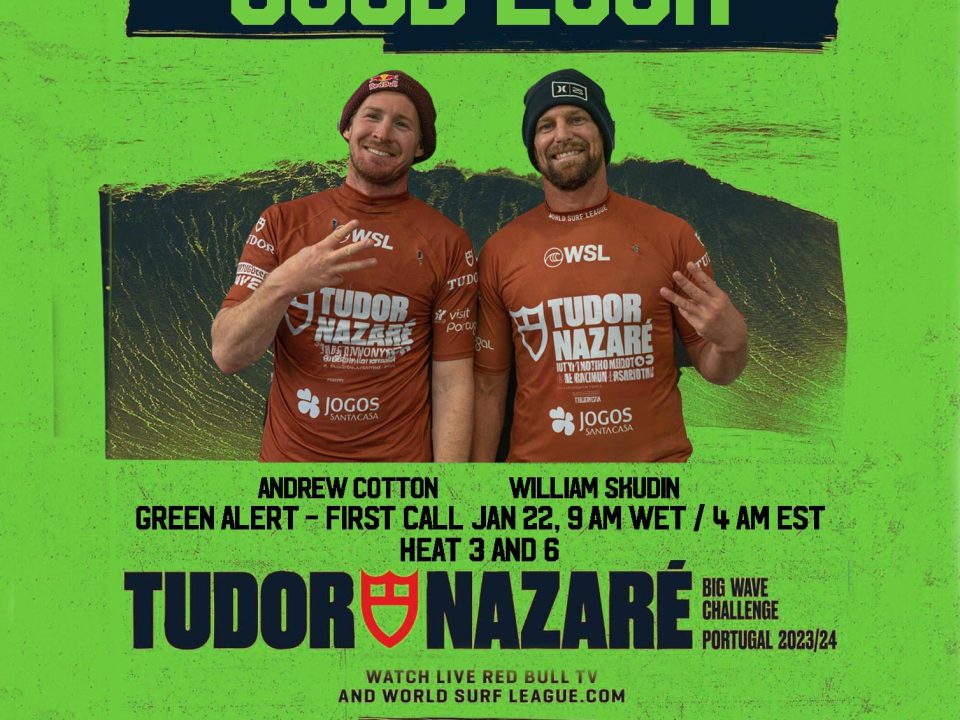

Organizing the cleanup effort was Will Skudin, then 27, along with his brother Cliff. With his beard and strong jaw, Will had the air of a mountain man. He began by dismissing the reports of locals looting: Long Beach, he said, was too tight-knit a community for that to happen. Then he thanked us for lending a hand in his town’s recovery.

I knew about Will Skudin from the surf media. A third-generation Long Beach surfer, he was the first veritable big-wave surfer ever to emerge from the East Coast. He had grown up idolizing Jay Moriarity, a surfer from Santa Cruz, Calif., best-known for a horrendous wipeout in 1994 at Maverick’s, Northern California’s lethal big-wave spot. The photo of it, which made the cover of Surfer magazine, shows Moriarity blown backward at the crest of a five-story brownish wave, his board pointing skyward, his arms flung out in crucifix position.

At 15, Skudin decided that he wanted to be the youngest goofyfoot (someone who rides with his right foot forward, a kind of left-handedness) to surf Maverick’s “at size” — waves of 25 to 50 feet. When he was 16, in 2001, he heard there was a swell on its way there and talked his father into allowing him to travel across the country to surf it. Watching from a boat in the channel at Maverick’s, Skudin’s father saw his son take a bad wipeout and assumed that would be the end of his infatuation with huge surf. But Will popped up with a smile and promptly went back for more. It’s this freakish response — whetted appetite — to a violent near-drowning that distinguishes the psyche of big-wave surfers, a tiny minority, from that of the rest of the surfing populace.

For me, surfing has always been bound up in making hard choices about what kind of life I wanted to live, where I wanted to call home.

I grew up on a different East Coast, that of Melbourne Beach, Florida, in the 1970s, but the essence of surfing was the same: pagan joy, scorn for the workaday world, membership in an alternative family. Like surfers everywhere we nursed a quiet pride born of plunging into what everyone else kept at a wary distance — the ocean at its most dangerous. In truth, it was less perilous than it appeared, though sharks could be a problem. I was injured a few times — once fairly seriously — but no one ever died surfing.

Big-wave riding was different. There was none on the East Coast, but in magazine photos and films Hawaii beckoned ominously, beauty and terror. The older, better surfers in my circle were making the pilgrimage there, where people did die surfing. By the time I was 15, I was sure I would follow — at which point my stepfather lost his job and we moved to Kansas. I lasted a little over a year in Wichita, but something shifted in me during that time, and when I returned to Florida to finish high school, I found myself dreaming not of big waves and palm trees but of big cities and books. I wanted to be a writer. Surfing fell by the wayside.

I had quit surfing in order to immerse myself in another, more or less opposite, way of life — night life, lamplight. That renunciation had seemed irrevocable and nothing, over the years in which held sway, led me to doubt its finality.

But when I stumbled into surfing again, during a kind of pre-midlife crisis, it reactivated fantasies of a life of sunlight and ocean, of immediate, full-bodied gratification, which had been lying dormant rather than dead inside me. Around that time, my younger brother moved to Kauai, Hawaii, and I had to master a strong impulse to throw aside everything in New York and join him there. Surfing retained the power to disrupt and reroute everything, just as it did on a smaller scale whenever a swell popped up and I dropped whatever I had planned for that day in order to go meet it.

All that day in Long Beach, hip-deep in debris and grief, I felt both more connected to the place and less so. Like Melbourne Beach — like hundreds of beach towns up and down the East Coast — Long Beach occupies a slender barrier island between the Atlantic and an estuary. While the waves had blasted apart the boardwalk and poured into beachside houses, the storm surge had pushed into the East Rockaway Inlet, brimming the intracoastal waterways. In the end, the worst flooding had come not from the ocean’s battering but from the stealthy creeping outward of these creeks and channels and wetlands. It was at a house on this estuarial side of town that I spent the day ripping soggy Sheetrock and water-damaged wiring from the walls, hauling sodden rugs and furniture to the curb.

But I had a hometown of my own, I kept reminding myself. I was not some rootless surf beggar. Yet my quitting surfing was bound up in leaving Melbourne Beach behind, a decision I never entertained the least doubt about until I began surfing again. Now I was occasionally haunted by guilt and longing when I thought of it, as if by moving away I had betrayed a purer, better version of myself — a self loyal to the place that had helped form and nurture it. My Will Skudin self.

The closest thing to big waves on the East Coast is hurricane surf. Typically a storm swings away from the Northeast coast and the weather is fine, the waves sizable and shiny. With Sandy it was different. On the morning of the day Sandy made landfall, the sky was a vast watery white-gray, and the waves were big but ominously dark and buffeted by a howling sideshore wind. Still, there were waves. Ignoring the usual stern warnings to stay out of the water, surfers paddled out. Will Skudin was briefly among them.

Then, as he later told me, he witnessed something he’d never seen before: A set of waves broke at dead low tide and washed hundreds of feet up the beach and under the Long Beach boardwalk.

It was time to go in.